Why is LVMH selling its 50% stake in Fenty Beauty? A case study in how celebrity brands burn out faster than their hype

LVMH is set to sell its 50% stake in Fenty Beauty, the brand founded together with Rihanna in 2017. This decision aligns perfectly with the new strategic priorities implemented by the group led by Bernard Arnault, at a time when the high-end beauty market is experiencing a phase of maturity and saturation. According to sources from Reuters, the sale will be assisted by the investment bank Evercore, which has already begun searching for potential buyers. Meanwhile, LVMH has not issued official statements, but the rationale behind the choice is clear. In a context of slowed growth, with a 4% decline in revenue in the first nine months of 2025, the group prefers to focus only on assets that strengthen its core holdings such as Dior and Sephora.

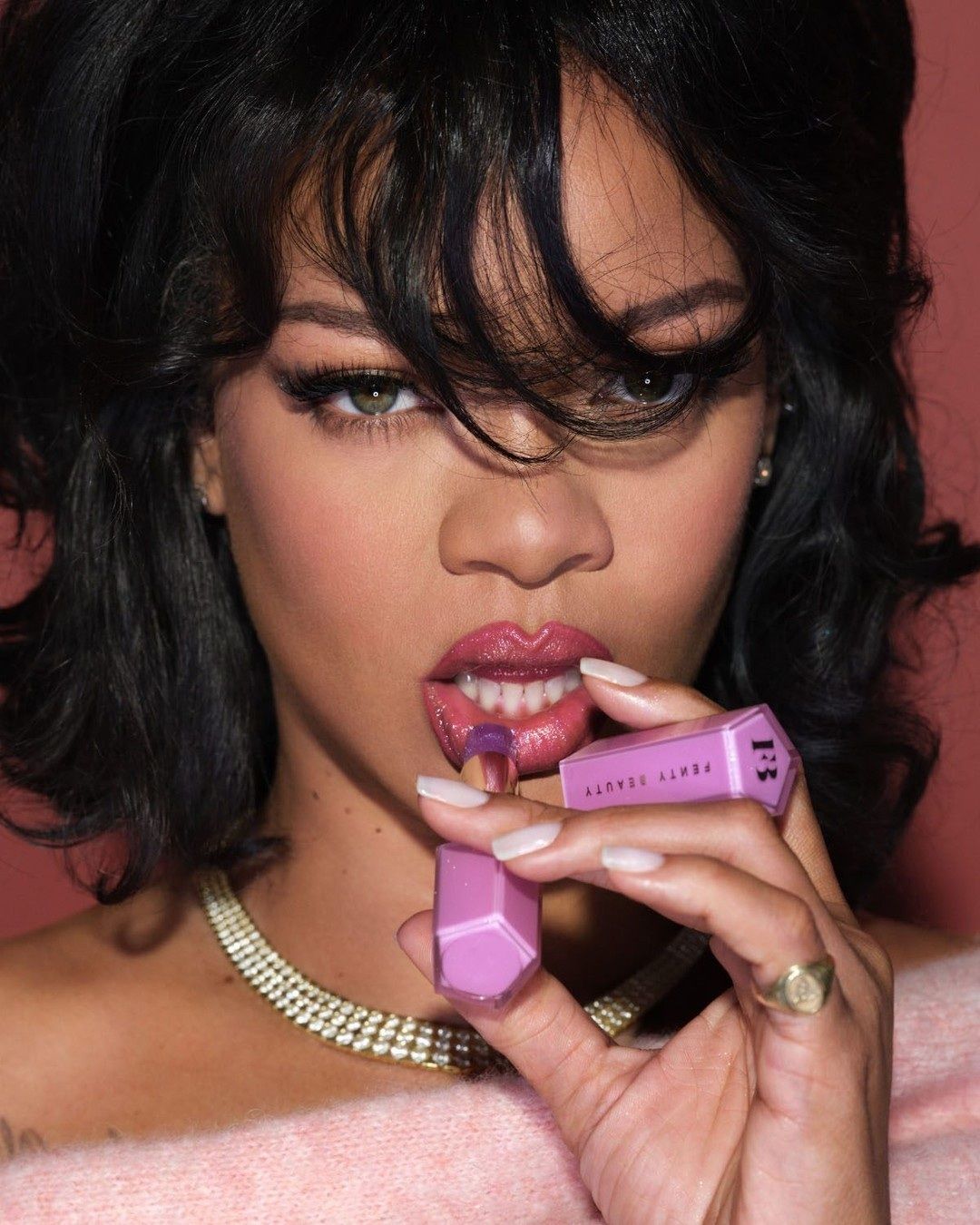

The rise and slowdown of an inclusive beauty revolution

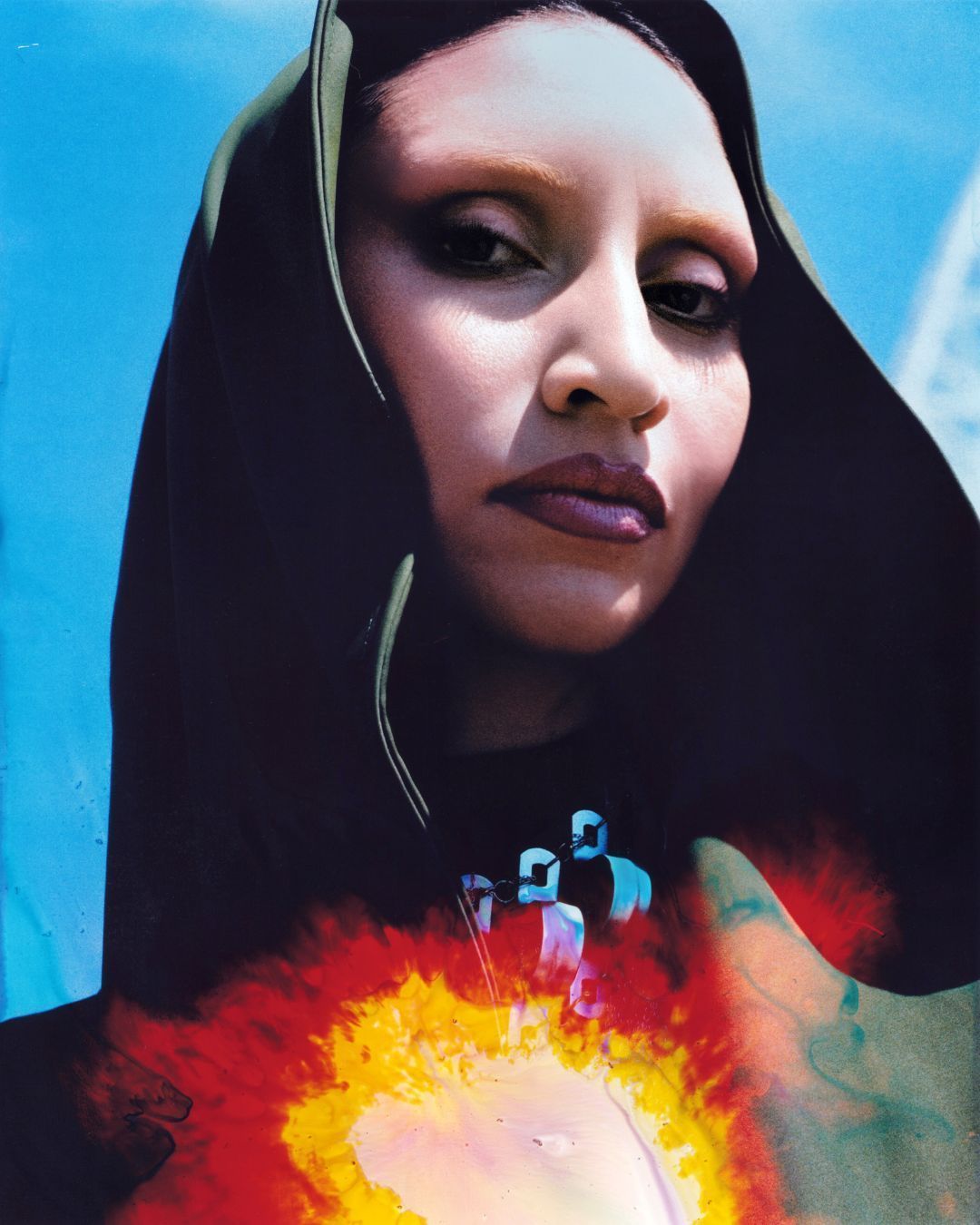

When Fenty Beauty launched in September 2017, it was a seismic shift in the world of luxury makeup. Rihanna, in collaboration with Kendo Brands (LVMH’s incubator for new cosmetic projects), launched a foundation range in 40 shades, redefining the very idea of inclusivity in beauty. It wasn’t just a product line, but a cultural manifesto. In its first year, the brand generated over $550 million in revenue, with an estimated valuation of $2.8 billion. For many, it represented the future model: a global brand, digital, progressive, backed by a celebrity with an authentic voice. But as happens with many charisma-driven revolutions, the fire eventually dimmed. Between 2023 and 2025, Fenty Beauty’s sales began to slow, particularly in North America. Not because the products declined in quality, but because the narrative ran its course. Rihanna remained an icon, but ceased to be the brand’s daily storyteller.

The borrowed relevance theory

Marketing scholar Camille Moore calls it borrowed relevance: the phenomenon in which a brand builds its credibility on the cultural relevance borrowed from a celebrity. It’s a model that works brilliantly in the short term, but has a natural expiration. In the case of Fenty Beauty, the brand-founder link was so strong that separation was impossible. As long as Rihanna embodied the brand daily, attending launches, creating content, and engaging with fans, the borrowed relevance was active and powerful. But when her attention shifted to other projects such as motherhood, music, or the Super Bowl performance, the brand lost its narrative anchor. As Moore explains in Art of the Brand on Substack, "borrowed cultural relevance can ignite a brand, but it cannot keep it burning."

The core asset test

For LVMH, beauty revolves around two poles: Dior as the creative and productive pillar, and Sephora as the global distribution infrastructure. Everything that does not strengthen one of these two assets is considered peripheral. Fenty Beauty, while representing a cultural milestone, is not integrated into this architecture. The group had already applied the same logic to Kendo, which gave rise to brands like Marc Jacobs Beauty, Bite Beauty, and Kat Von D Beauty. Over time, all were closed or sold. The reasoning is always the same: they do not generate strategic leverage. Fenty, therefore, is not being sold because it is underperforming, but because it is no longer essential. A brand can be profitable and, at the same time, not be "core."

When fame isn’t enough

In 2017, millions of people bought Fenty Beauty because Rihanna created it. It was an implicit promise: "If Rihanna uses it, it’s right for me too." But fame does not generate repeat purchases. Competence, product quality, and consistency over time do. This is the key difference between celebrity brands and those founded by professionals. Moore cites examples like Huda Kattan, Pat McGrath, and Bobbi Brown. These makeup artists built their brands on years of authority and expertise, creating products born from a professional vision, not a fame aura. They rely on what Camille Moore calls earned authority, authority gained, not borrowed. It’s the difference between a flame and embers: the flame attracts attention, but the embers endure.

Why is LVMH selling its 50% stake in Fenty Beauty?

LVMH has realized that celebrity brands are not platforms, they are products. A product has a lifecycle: it is born, grows, matures, and declines. A platform, instead, accumulates value over time: the longer it lives, the more credible, authoritative, and rooted it becomes. Fenty Beauty never became a platform. It remained a powerful project but dependent on the energy of its founder. When that energy shifted, the brand began to cool. For a conglomerate like LVMH, which operates on long-term cycles and intergenerational brand equity, the lack of strategic depth is reason enough to exit. Selling the stake in Fenty Beauty is not just a financial operation; it’s a warning for 21st-century brand builders. If your brand’s value is based on fame and not on expertise, you are building a time-limited success. Celebrity brands don’t fail because they lose charm; they fail because they exhaust the borrowed attention they once had. Camille Moore calls this a dynamic of expiration. Whenever a brand depends on a public figure for relevance, its actual lifespan is tied to that figure’s attention cycle. LVMH is not disowning Rihanna or disregarding Fenty Beauty. It is simply exercising the luxury of clarity. By cutting what does not strengthen its core, the French group demonstrates a discipline that many brands struggle to apply.