Women, myths and popular resurrections The red thread that connects art to paintings, from Doechii onwards

A subtle thread connects the centuries: from mythological figures to pop artists, every time the female body chooses to speak to itself and to the world. The body as both relic and rebellion, stage and confessional. From baroque painting to digital platforms, the image keeps oscillating between sacrifice and power, guilt and desire. Today’s artists redraw the atlas of images with a new awareness. They know they belong to a genealogy of exposed and re-signified bodies. Their voices and gestures become rewritings of myth. Thus Salome, Judith, Joan of Arc, and Medea return to the stage, transforming the wound into a performance of redemption.

Nina del Sud / Caravaggio – The Revenge of the Gaze

In Salome with the Head of the Baptist (1607), Caravaggio strips the myth of its theatricality and reduces it to the essential: a face, a severed head, a young body observing. The scene is intimate and merciless. Salome neither revels nor repents; she bears witness to an irreversible act and, at the same time, to the birth of a new consciousness. It is the female gaze that, for the first time, returns the violence it has suffered: Caravaggio paints a woman who observes, not one who is observed. And in that shift, he overturns the entire iconography of guilt.

@nssgclub Abbiamo assistito alla performance de @LA NIÑA allo show di Etro SS26, per la Milano Fashion Week. Cosa ne pensi? Faccelo sapere nei commenti. #laninadelsud #lanina #etross26 #performance #mfw original sound - nssgclub

Nina del Sud moves along that same edge. In her Salome, song becomes a tool of revenge and rewriting—a way to respond to an imaginary that for centuries has turned women into surfaces to be interpreted. Her voice, warm and razor-sharp, takes on the role of Caravaggio’s light: it reveals, dissects, redeems. There is an irony that dismantles tragedy, a melancholy that keeps it from indulgence. Desire, in her songs, is dense with a language of reclamation: a code through which to speak of power, shame, and pleasure without submitting to any of them.

In the symbolic act of asking for the prophet’s head, Nina doesn’t kill the man but the idea of purity that has always imprisoned her. Her Salome is a pagan, Mediterranean ritual, made of sun, sweat, and irony, where revenge is not violence but clarity. Like Caravaggio, Nina works with chiaroscuro: between vulnerability and ferocity, sacredness and sensuality, she builds a femininity that no longer needs justification. In her sonic world, blood becomes rhythm, and the blade, melody. The act of decapitation becomes creative: an aesthetic liberation in which body and voice coincide, defend, and multiply themselves. If Caravaggio painted the moment when beauty blends with threat, Nina del Sud sings the instant when threat turns into art where guilt dissolves into sound.

Doechii / Artemisia Gentileschi – Gesture and Justice

In Artemisia Gentileschi’s painting, Judith Beheading Holofernes (1612–1620), the gesture is everything. The plunging blade is not just a weapon but a line of truth, traced by a hand that knows the measure of justice. Artemisia, having survived violence and marginalization, paints not a moment of revenge but one of absolute lucidity. In that terrible and perfect balance, painting becomes an instrument of repair, a way to rewrite the female body not as victim, but as agent of its own destiny.

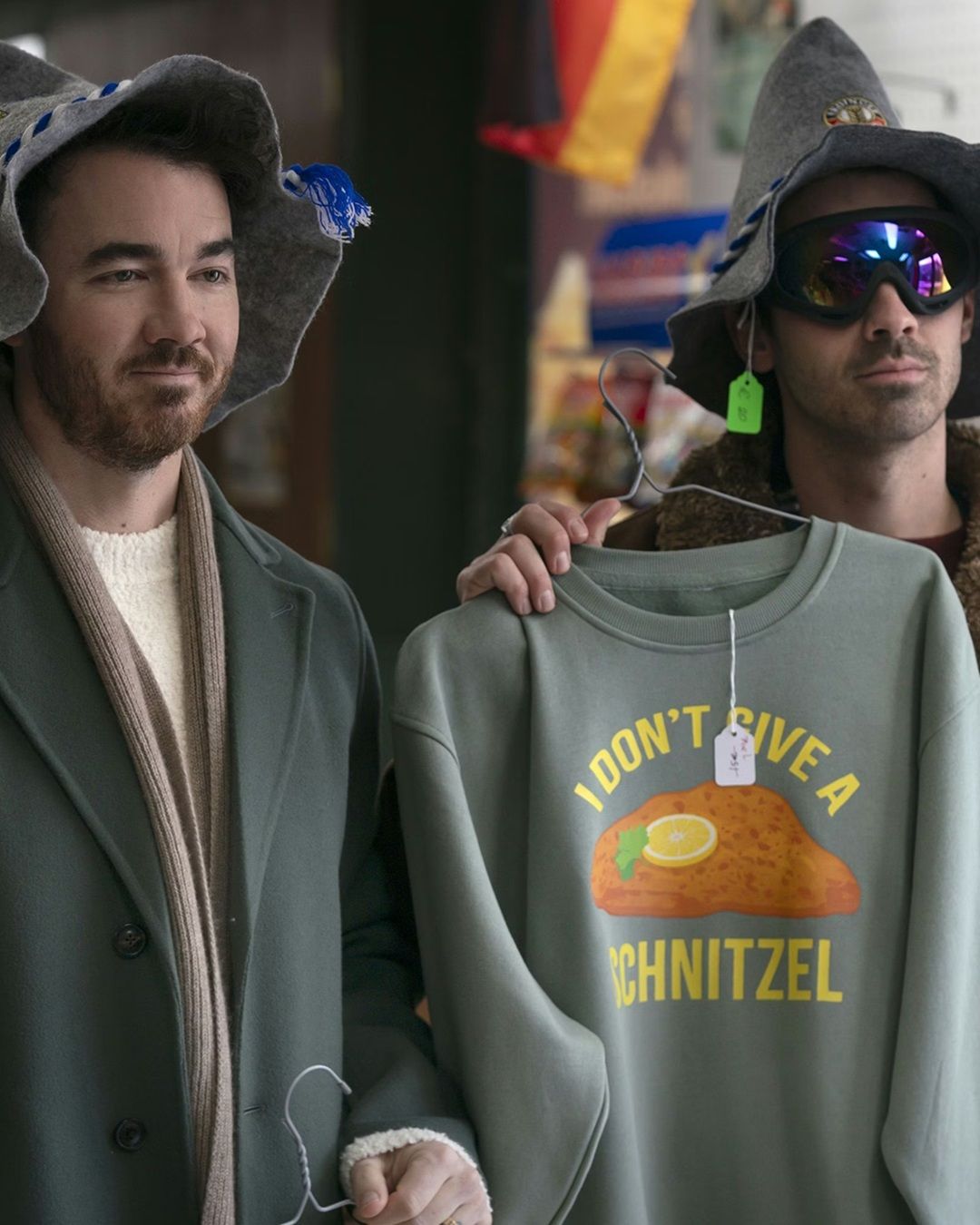

Doechii, with her stage presence and radically self-determined writing, embodies that same tension. Her performances don’t seek approval, they claim space: the body that sings, dances, and commands the stage doesn’t represent femininity, it defines it each time. If Judith wields the sword, Doechii wields the microphone and the gesture different in form, but carrying the same political and poetic urgency. In her songs, theatricality becomes a strategy of power: disguises, bursts of irony and anger build a language that disarms the male gaze and reverses the paradigm of pleasure.

Like Artemisia, Doechii turns the wound into grammar, trauma into aesthetics. One paints with thick strokes of blood and light; the other writes with beats and words that oscillate between confession and revolt. Both conceive justice not through pity but through awareness of the gesture: knowing where to strike, when to stop, how to show strength without losing grace. On stage, Doechii moves like a modern Judith, offering us a form of performative justice that is also catharsis. In both, art becomes a symbolic tribunal where the woman is no longer the object of the story but the subject of truth. The sword, the voice, the light: three instruments for the same purpose, turning pain into gesture, gesture into justice.

Nava / Millais / The Amazons – Faith in the Fire

In Joan of Arc (1865), Millais doesn’t simply paint a Christian heroine but a body crossed by the mystery of faith: his Joan is infused with light, suspended between the fervor of martyrdom and the sensuality of a young woman listening to her inner voice. The whiteness of her robe, the metallic sheen of her armor, the verticality of her gaze build a tension that is both ascetic and erotic. An ecstasy born from direct contact with the divine, yet also from the recognition of her own corporeality. In this duality, Millais translates faith as an embodied experience, where the invisible takes shape in the flesh. Spirituality becomes vision and desire, revealing that the sacred is not opposed to the sensual but is its deepest extension.

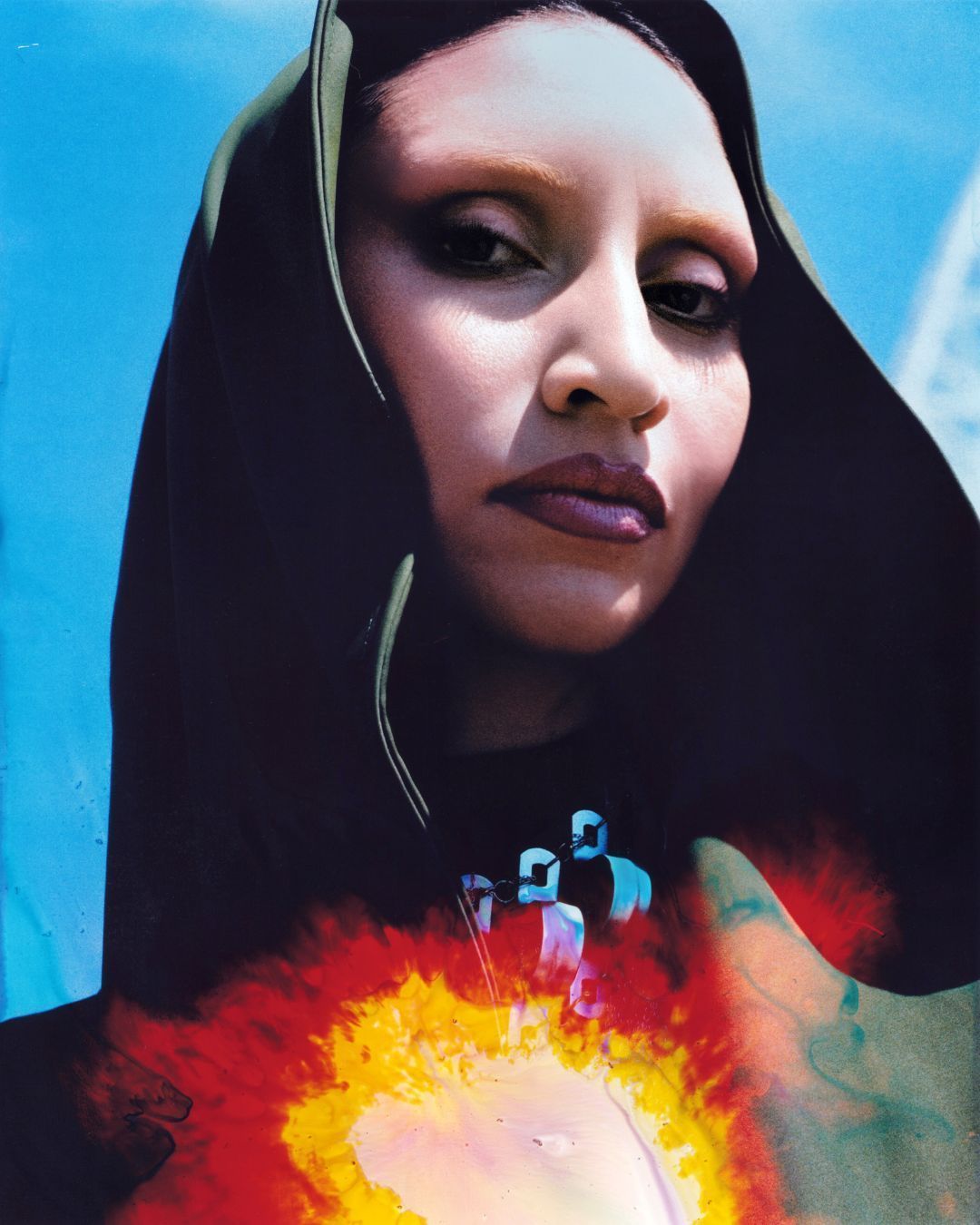

Nava seems to channel that same tension, translating it into the language of the present: her “faith in the fire” is a devotion to image, sound, and creation as a form of transcendence. In her works, spanning video, performance, and electronic music, the body becomes the medium of a secular, post-human ritual, where LED light and skin treated as sacred surface evoke a mystical aesthetic infused with digital culture. The artist moves through the visual space like an icon aware of its own artificiality. In that awareness, Nava tells a form of truth: faith in the construction of identity, in the possibility of transforming ornament into spiritual language.

The parallel with the Amazons amplifies this dimension. No longer archetypes of a warlike or mythological femininity, but collective figures of a new shared sacredness, sisters in vulnerability and strength. Like them, Nava crosses the boundary between body and symbol, between human and divine, to restore an image of woman as creator and bearer of language. Hers is not a dogmatic but a performative faith, one that manifests in the very act of generating beauty, rhythm, light. Nava listens to the synthetic echo of the digital world and turns it into song: a prayer that unites spirituality and technology, flesh and circuit. In her aesthetic universe, fire does not burn, it is the alchemical substance that transforms, that returns to faith its creative potential. As in the Pre-Raphaelites, the sacred is no longer tied to religion but to a total aesthetic experience: a faith in the image as an act of truth, where beauty still has the power to generate visions.

Sienna Spiro / Medea – The Lucid Disaster of Love

Medea is the woman who loves until she betrays herself, the foreigner who leaves her homeland to follow Jason and, once betrayed, turns pain into a declaration of clarity. In Euripides’ tragedy, Medea understands that the loss of love is also the loss of role, language, identity, and decides to rewrite her story at the cost of destruction. Sienna Spiro sings from that same place of awareness. Her compositions, steeped in melancholy and conceptual precision, restore love to its corrosive power, to the analytical gaze of one who doesn’t wish to heal but to analyze, dissect. Hers is an inner Medea, where the voice rises again from trauma. In her lyrics, feeling is an obsessive study of pain, an alchemical process in which vulnerability becomes a form of cognitive power. If the other heroines decapitate, Sienna recognizes the fracture: her weapon is emotional, disenchantment, the precision with which she turns disappointment into knowledge. In her, Medea is no longer the monstrous infanticide but the first philosopher of betrayed love.

In this contemporary pantheon, Salome, Judith, Joan, and Medea are no longer relics of the past but living presences, reborn through the artists who today redefine womanhood through music, performance, and image. Their myths, once confined to canvases and tragedies, now pulse through digital screens, music videos, and live stages: new altarpieces where the sacred and the profane collapse into one. Pop, far from being mere spectacle, becomes a form of modern mythology, a living archive where the body carries both its scars and its revelations. The new saints do not seek forgiveness; they sing from the wound, turning pain into rhythm, memory into power, and silence into prophecy.